Commentary by Jim Emberger, The Daily Gleaner, The Times Transcript, August 19, 2021

Martin Wightman’s recent column on the future of natural resource mining in Canada (“Don’t let China corner the market on critical minerals”) made some valid points – but also had some serious oversights.

As part of the decision process surrounding future mining projects, he says we should “mitigate the environmental concerns of mining and ensure local communities aren’t decimated.” I’m sure most people would agree with this. But then he makes the contrary suggestion that we must also reduce government regulations on mining, and change our “attitude” toward it as well.

To illustrate these opposing statements, he chooses the example of the proposed Sisson mine. He could not have picked a worse example to make his case, because it negates both of his theses.

Wightman notes the mine was proposed in 2013 and still has not yet started, inferring that government regulations and citizen opposition are at fault.

The real reason there is no mine is that the proponents have not been able to obtain the necessary financing, despite trying for eight years. There is a simple reason for that: the low price of tungsten has repeatedly thrown the viability of the project into question. So the project has stalled, in spite of the government working hard to approve it.

For example, the conditions for approval laid out in 2015 required the proponent to submit a fiscal plan on which to judge the project’s viability. The plan is years overdue and the government has not enforced the condition or provided a reason for not doing so.

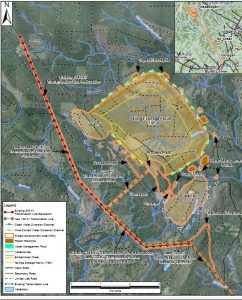

Source: Sisson Brook EIA: (https://www2.gnb.ca/content/dam/gnb/Departments/env/pdf/SissonProject-ProjetSisson/Summary.pdf)

The project was also required to start within five years or else face an entirely new Environmental Impact Assessment. Yet the project did not start on time, so the government simply granted it a two-year extension.

Ironically, the government’s willingness to make things easier and cheaper for the proponent has created an active local opposition movement, where once there was substantial community support.

For one thing, this mine will create an enormous amount of toxic tailings. The proponent wants to create an earthen dam, kilometres long and taller than the Macquatac Dam, to hold the tailings in a lake that would sit near the headwaters of the Nashwaak River. It would need to be monitored and require pumping and potential treatment and maintenance in perpetuity.

This is the same kind of earthen mining dam as the Mount Polley Dam in British Columbia, which several years ago collapsed and poisoned lakes, drinking water sources, waterways and salmon spawning areas. Global statistics show that, at a minimum, three to four such earthen dams collapse every year.

A collapse at Sisson Brook could devastate the Nashwaak watershed, one of the cleanest rivers in the province.

To date, Northcliff Resources, the company behind Sisson, hasn’t demonstrated that it even has the money to post required bonds for reclamation, fish habitat compensation and post-closure water treatment.

So, quite naturally, local residents instead called for the tailings to be “dry-stacked,” which is a safer method and one favoured by many mining engineers. The government, of course, approved the dam. This is only one of many environmental insults to the community contained in the approved Environmental Impact Assessment that have mobilized community opposition.

Wightman’s insinuations that red tape or community opposition are responsible for Canada’s lack of mining development is simply the same tired line that has been trotted out by resource developers wherever and whenever they have existed. It is their mantra, but unfortunately, it is not true.

Perhaps, therefore, instead of blaming red tape and community opposition for failures, we should blame poor economic planning and failure to determine the quality of proposals, the government’s eagerness to support any development that promises jobs, and the total dismissal of environmental and social concerns from local residents.

As Wightman notes, Canadian mining companies’ environmental and social records looks best “in comparison to nearly everywhere else.” Many of these other places are where Canadian mining companies are operating in countries without strict government regulations, places that lead the world in environmental and human rights abuses.

Wightman’s standard is one we should not find too comforting, and certainly doesn’t make his case for reducing regulations.

Certainly we will need to mine some natural resources, but not at the expense of the environment and our future, which is what we will be destroying if we ease regulations on mining companies.

As both climate change and forest destruction are now teaching us, we need stronger regulations, not weaker ones.

Jim Emberger is Spokesperson for the New Brunswick Anti-Shale Gas Alliance